4 hours ago

Enchanting Rebellion: “100 Nights of Hero” Invites Us Into a Queer Fairytale for the Ages

READ TIME: 4 MIN.

Imagine a universe where the only thing more dangerous than a husband’s bet is the spark between two women who refuse to be written out of their own stories. Enter “100 Nights of Hero” — the latest genre-defying fairytale from director Julia Jackman, which just made waves at the Venice Film Festival and is set to become a new queer classic . Adapted from Isabel Greenberg’s beloved graphic novel, the film unravels the tale of Cherry (Maika Monroe), her shrewd and devoted maid Hero (Emma Corrin), and a castle filled with lust, longing, and the world’s worst game of marital chess.

The premise is deliciously audacious: In a society worshipping the whims of the egotistical BirdMan (a scene-stealing Richard E. Grant), Cherry is treated as little more than a pawn in the game of inheritance and masculinity . Her husband, Jerome, is more interested in making bets than in consummating their marriage. So, when Jerome wagers with his boorish friend Manfred (Nicholas Galitzine) that Cherry will remain faithful for 100 nights — or else lose his castle and his wife’s freedom — a sinister countdown begins .

But where most stories would spotlight the cat-and-mouse of male rivalry, “100 Nights of Hero” subverts expectations. Cherry’s true connection is with Hero, her quick-witted companion whose stories become both shield and solace. As Manfred struts, seduces, and slaughters his way through the castle in a parody of toxic masculinity (shirtless stag-slaughter, anyone?), Cherry and Hero’s bond deepens — their intimacy burning quietly, defiantly, beneath the surface .

What sets “100 Nights of Hero” apart isn’t just its central romance, but its reverence for storytelling itself — a motif that resonates deeply within queer history. When the world is hostile, stories become lifelines and weapons. Each night, as danger draws closer, Hero spins tales of rebellious women and forbidden love, weaving a tapestry of resistance that offers hope to Cherry and, by extension, to every viewer who’s ever been told their desires are unspeakable .

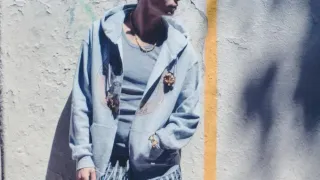

One standout subplot follows Rosa (played with wild abandon by Charli XCX), whose own ill-fated romance with a merchant echoes the central themes of love, risk, and the price of living authentically . While the patriarchal world worships cautionary tales — Janet the Barren, Sara the Unfaithful, Nadia the Lesbian — Hero’s stories rewrite the rules, offering not just escape, but the promise of a different future.

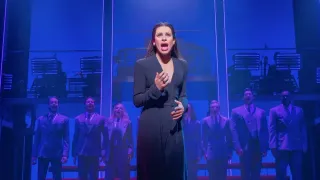

The film’s magic is amplified by its cast. Emma Corrin, magnetic as Hero, brings both mischief and gravitas, while Maika Monroe finds aching humanity in Cherry’s repression and yearning. Their chemistry is electrifying, dialed up by sumptuous period costumes and production design that flirt with the conventions of stuffy historical drama, only to gleefully upend them .

Nicholas Galitzine, fresh from queer fan-favorite roles, leans into Manfred’s villainy with a blend of swagger and satire, lampooning the very idea of heterosexual conquest. Charli XCX, meanwhile, steals scenes with her portrayal of Rosa — her performance a wink to queer pop stardom and rebellion. These choices feel intentional: a celebration of queer joy and a jab at the rigid binaries that so often define “traditional” fairy tales .

For LGBTQ+ audiences, “100 Nights of Hero” arrives as a breath of fresh, enchanted air. Its love story is not just an add-on or a subtext; it is the engine of the narrative, pulsing with wit, warmth, and urgency. In a media landscape still catching up on queer representation, especially in fantasy and period settings, the film’s unapologetic queerness feels radical and necessary .

Moments from the official trailer — “Tell me, what does it feel like to be wanted?” and “Meeting you, that’s been the greatest adventure of my life” — are already echoing across queer social media as affirmations of longing and hope . These aren’t just lines; they’re rallying cries for anyone who’s ever yearned for a love story that feels like theirs.

At a time when queer rights face renewed backlash in parts of the world, “100 Nights of Hero” doesn’t just tell a story — it plants a flag. Here is a world where queer love is not punishment, but possibility; where the act of telling your story is an act of revolution . The film’s sharply satirical view of patriarchal power makes its victories all the sweeter for LGBTQ+ viewers who know all too well the dangers of being cast as cautionary tales.

For every queer person who has ever found safety in a friend’s story, or courage in a forbidden glance, “100 Nights of Hero” is a reminder: we are the heroes, and our stories deserve to be told — not just for 100 nights, but forever.

With its fearless heart, biting humor, and spellbinding performances, “100 Nights of Hero” joins the growing canon of queer fairytales rewriting what happily ever after can mean . It’s a film for anyone who’s ever wished for a love story that doesn’t settle for the margins — and, in the words of Hero herself, “the greatest adventure of my life.”